Thirty-One: Losing It and Loving It

ABML examines the virtues of non-sense, from Alan Watts to the Beatles

These aren’t what you’d call fun times. The need for laughter is greater than ever. So let’s get metaphysical and see if it takes us somewhere fun.

The ancient Vedic tradition in India interprets all of creation as Vishnu lila, the “Play of Vishnu.” The Sanskrit word lila translates as dance or play. The same tradition positions the phenomenal world as illusion, or maya.

Lila is connected to the root lelay, “to flame,” “to sparkle,” “to shine.” Lelay carries connotations of fire, light and spirit. Cosmic creation is conceived not just as a divine game, but as a play of flames, the dancing of a well-tended fire.

Sanskrit traditions conceived of fire as an elementary manifestation of divinity because fire combines radiance with playful movement. The concept of maya takes on a subtler meaning in this context. To tear the veil of maya and reveal this cosmic illusion amounts to understanding its core purpose as “play” – the “free, spontaneous activity of the divine” in the words of anthropologist Mircea Eliade.

In Latin, the root of the word illusion is ludere, to play. Ludere, lunettes, illusion, lucidicity, luminescence, and illumination are cross-referenced semantically and phonetically in Latin, French and English.

And let’s not forget the lightweight connotations. When British author G.K. Chesterton wrote that “angels fly because they take themselves lightly,” he put another accent on the many meanings of light — as in the opposite to heavy, burdensome and serious. The very things that are the opposite of play.

And that roundabout but hopefully not exhausting excursion into etymology brings me to the subject of humour.

Laughter clubs

Some years back, “laughter clubs” began popping up across the world, from India to China to East Vancouver. Many are still around. The sole purpose of these gatherings is for participants to laugh at nothing whatsoever for extended periods of time.

I tried a variation of this myself one summer at a yoga retreat on the Canadian west coast. I lay with a group of a dozen people in a field, with the back of my head resting against the stomach of a stranger, who had his head against someone else’s stomach, and so on, in a herringbone line-up of participants. The instructor advised the first prone person in this line-up to not laugh — a difficult thing to do given the absurdity of the situation. As her belly jiggled, the head of the next person bobbed up and down and she began to laugh in response. Laughter exploded along the reclining participants like a line of firecrackers. How could you not crack up when your head was leaning against someone who was convulsing with laughter?

The purpose of this seriously silly exercise was to get the participants to experience the force of pure, context-free laughter. Health experts know plenty about how laughter benefits the immune system. Still, laughter clubs may seem a bit strange to some westerners. They run counter to the persistent notion among WASPS that self-improvement shouldn’t be difficult and time-consuming. Aren’t they casting shade on more serious efforts at personal upgrades, whether through yoga, meditation, exercise, education, work or religious instruction?

Perhaps our ideas of happiness-as-birthright and our sombre efforts to get there are part of the problem. There’s no shortage of advice from the media about what we need to be happy and how to get it, yet this always seems to involve a heap of credit. Advertisers tempt us with amazing lifestyle possibilities, but few of us will become bodhisattvas with washboard stomachs and eighty-foot yachts.

The end result is that a complete life of satisfied goals is always receding into some imagined future. It feels like a rigged game, with the pot of gold as vaporous as the RRSP rainbow leading to it. As author Tom Robbins observed in 2003, it may seem a tall order cultivating a rich inner life in a culture “… whose institutions — academic, governmental, religious and otherwise — seem determined to suffocate it with a polyester pillow from Wal-Mart.”

Robbins had a way out in mind:

“Unbeknownst to most western intellectuals, there happens to be a fairly thin line between the silly and the profound, between the clear light and the joke, and it seems to me that on that frontier is the single most risky and significant place artists or philosophers can station themselves.”

This doesn’t just apply to artists and philosophers; it’s a risky business for anyone to wear the fool’s peaked cap into a respectable setting. Yet membership has its privileges, starting with the fact that there are no monthly dues in the fools’ borderless club.

Robbins himself was a practitioner of a kind of foolish literature that never fit easily in the literary canon. The East Coast lit-crit establishment favours writers who traffic in trauma-based narratives in either fiction or memoir. Somber books endorsing the idea of an unfriendly, random universe are often the ones deemed timeless masterpieces. Describing a book as “difficult” is considered a recommendation rather than a red flag. This holds true for the rest of the “serious” arts as well. If you’re a cultural creative in search of an arts grant, obscurity helps. And if you must have humour, it better be of the gallows variety. If you go for absurdity, make it in the spirit of Kafka rather than Cleese.

In his 1909 essay A Defense of Nonsense, UK writer G.K. Chesterton praised a higher form of foolishness found in the writings of Lewis Carroll:

We know what Lewis Carroll was in daily life: he was a singularly serious and conventional don, universally respected, but very much of a pedant and something of a Philistine. Thus his strange double life on earth and in dreamland emphasizes the idea that lies at the back of nonsense – the idea of ‘escape’… into a world where things are not fixed horribly in an eternal appropriateness, where apples grow on pear trees and any odd man you meet may have three legs.

Lewis Carroll, living one life in which he would have thundered morally against anyone who walked on the wrong plot of grass, and another life in which he would cheerfully call the sun green and the moon blue, was, by his very divided nature – his one foot on both worlds – a perfect type of the position of modern nonsense. His Wonderland is a country populated by insane mathematicians. We feel the whole is an escape into a world of masquerade; we feel that if we could pierce their disguises, we might discover that Humpty Dumpty and the March Hare were professors and Doctors of Divinity enjoying a mental holiday.

Today we have two extremes of officially-endorsed absurdity. The first is the scientific interpretation of a random universe ruled by mindless forces to no particular purpose. The second is the religious fundamentalists’ take on ancient myths, complete with a temperamental God (or Gods) as unpredictable as electrons and as arbitrary as Alice’s Red Queen.

It seems there are few options between the two extremes of faith and faithlessness. There’s a folk misinterpretation of quantum theory found in New Age books, in which the observer “creates” his or her reality, a half-truth that can only inflate the ego. It’s not that the solipsistic visions are crazy, it’s that they’re not quite crazy enough. As Sir James Jeans wrote prophetically in 1933, “The universe may not only turn out to be queerer than we imagine, but queerer than we can imagine.”

The Sense of Non-sense

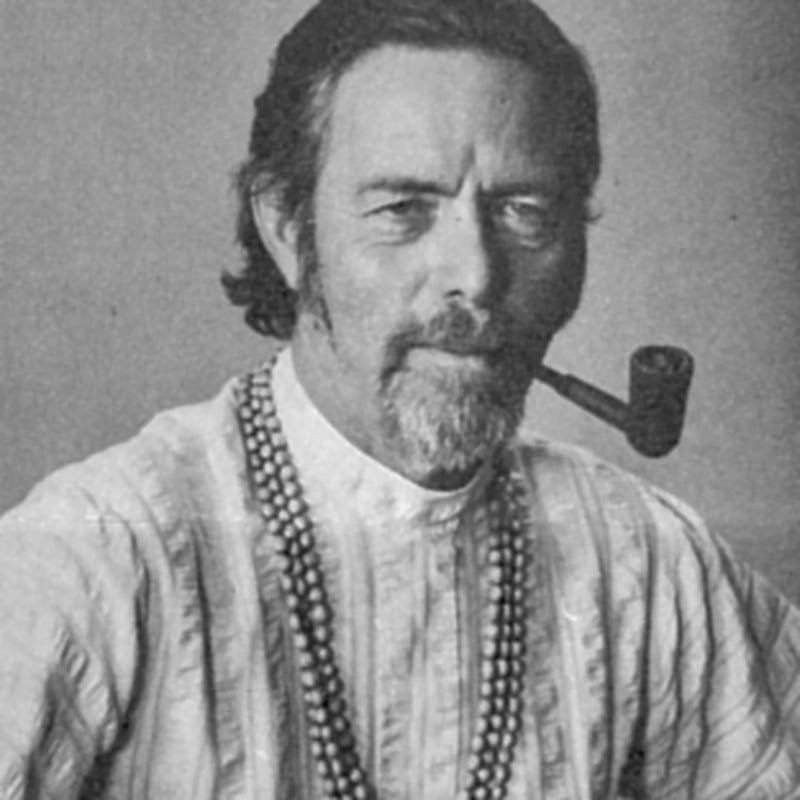

So where does that leave us? A half century ago, Zen philosopher and writer Alan Watts offered a unique perspective on meaning and meaninglessness. In his lecture “The Sense of Non-Sense,”he addressed the persistent human search for meaning, which has driven not only the highest productions of the arts and sciences, but the worst excesses of religion and politics as well.

Watts argued that the universe has no meaning, at least not in the semantic sense, because only words have meaning, signifying things beyond themselves. The set of letters that spells “fork” is not, itself, a fork. How could the universe – all that there is and ever will be – signify anything beyond itself? The cosmos, Watts insisted, is a system of patterns at play, a loom of electromagnetic waves weaving a tapestry of ever-changing themes. He insisted the whole shebang has a great resemblance to music and dancing, which in themselves make no sense because they’re not intended to mean anything other than what they are. The meaning and the activity are one and the same.

Watts asked us to consider baroque music, which obviously doesn’t signify any abstract ideas, but neither does it express some concretely expressible emotions. “It is felt to be significant not because it means something other than itself, but because it is so satisfying as it is.”

A sense of meaninglessness is adjacent to hopelessness, but there’s always someone ready with a remedy. “So many activities into which one is encouraged to enter, philosophies one is encouraged to believe in, religions one is encouraged to join, are commended on the basis of the fact they give life a meaning,” Watts observed.

Such belief systems offer an escape hatch from the sinking ship of nihilism, the dead end that often results from believing in a purposeless world. But what, he asked, does it mean that life has to have a purpose? We feel life ought to have significance beyond a mere symbol for something else.

Hence the appeal to ultimate answers, notes Watts, a former Episcopalian priest who ended up rejecting the Church. “In all theistic religions, the meaning of life is God himself in the world. It means a person. It means a heart, it means intelligence. The relationship of love between God and man is the meaning of the world, and the sight of God is the glory of God.”

What exactly is this glory is supposed to mean? What are the angels in heaven doing, Watts mused, when they fly around God in Heaven in Judeo-Christian iconography? Supposedly, they’re singing “hallelujah.” And what is the significance of this semi-musical expression of discarnate beings? None. It is an expression of pure joy, he insisted. The angels might as well be saying, “O-bla-di, O-bla-da,” or “Hey ho, let’s go.”

The author was not endorsing the concept of literal angels; he was demonstrating that even in the sober, otherworldly images of Christianity, there is an implicit appreciation of the virtues of non-sense.

Saying the universe is without meaning is not the same as saying it is all a random affair in which sentient beings emerge by accident. It’s not insisting the whole production is necessarily Mindless, either. It’s simply saying that meaning is a verbal notion we map unto something ultimately unknowable and that it is beyond categories. But there is another kind of meaning: the kind that is not puzzled over, but deeply felt.

In and Out of The Moment

In certain quiet, composed states of mind, free from the busy mental games of judgement and analysis, we may suddenly find significance in odd things. There are certain photographers who can capture a wall with peeling paint or some other mundane scene and turn it into something close to transcendent. They know how to capture it and sometimes convey it to viewers. The deep significance of life collapses to what sits nakedly before you. Meaning is contained in the moment.

Hence Aldous Huxley’s chemically-altered discovery in The Doors of Perception, when he found, quite to his surprise, an inexplicable sense of clarity gazing at the folds of his own trousers. (A more understandable and common example is when you find yourself absorbed by a particularly beautiful sunset or vista.)

These states of mind, which can sometimes emerge naturally, without drugs, fasting or some obscure mind-body discipline, are far removed from our usual problem-solving modes of thought. They’re distantly related to the inverted wisdom of that champion navel-gazer, the “fool.”

The fool is the person — typically male — who isn’t going anywhere. He has no ambition; he doesn’t even fight for himself. From the stories of Taoism to Shakespeare to Hollywood, the fool has always been used as a kind of analogue of the sage. He’s the one who is allowed to utter uncomfortable truths because no one takes him seriously anyway.

The fool of tradition has a closer connection to immediate things. He knows something the rest of us don’t. As Lao Tzu put it in The Tao Te Ching, “He who knows doesn’t speak. He who speaks hardly knows.” The fool is also closely related to the Trickster, a deceptive animal spirit universal to world mythology. The Trickster’s gig is to introduce chaos to human affairs, breaking taboos and making a mockery of our mental and social divisions. Frequently encountered at crossroads and borderlands, the Trickster is often the victim of his own pranks. Echoes of the archetype live on today in carnivals, circuses and TV sitcoms and cartoons (the coyote is both a Trickster figure in aboriginal legends and Warner Brothers’s Merry Melodies).

Back to Lila

Watts, who was never afraid of sounding a bit foolish himself, believed that the universe exists “... because the flame is worth the candle.” The manifest realm of all beings, subject to every conceivable experience, from heavenly to hellish, is an adventure that must somehow be worth having, for it to have come about at all. Of course, the author had no proof for this metaphysical claim. It’s his own unsatisfactory response to that unanswerable question: “Why is there something rather than nothing?” It’s an unsolvable riddle we can better approach through myth rather than science.

In interpreting Eastern philosophy, westerners tend to focus on the idea of maya, the realm of illusion resulting from the ignorance of our true being. The word has mostly negative connotations of trickery, deceit and forgetfulness. What gets relatively less attention is the flip side of maya, which is lila, the divine play or game of life.

In the Vedic system of thought, the sleeping “Cosmic Self” dreams up the entire play and all the actors in it, taking on their roles simultaneously and forgetting itself in the process. The game is to peer out through billions of eyes, from ladybug to businessman, in a vast illusion of separation and forgetfulness spanning billions of years. Lila is the tricksterish, game-like part of this cosmic self-deception. As I noted above, the word lila means the play of the divine, creating freely. Lila creates for the joy of it, out of spontaneous creativity, rather than through any need, lack, or desire.

There is a seductive poetry in this concept from the East, if only because we occasionally find it echoed in our personal experience. We commonly speak of “losing ourselves” when we’re fully engaged in a game, athletic performance or a sensual or artistic experience. And given our collective fear of personal death, it’s ironic that a subtle form of death occurs when we are happily “absorbed” in the world of imagination, laughter, or sensual delights. The ego temporarily vanishes. We are at our best, or at least feel our best, when we disappear into the moment. (It is not for nothing that orgasm is referred to in French as le petit mort or ‘the little death’.)

This is what makes “non-sense,” in the spirit Chesterton, Robbins and Watts intended, such a necessary antidote to the toxic varieties of nonsense we’re subjected to daily. Free-spirited fun enables us to drop our socially-constructed selves and partake in a kind of exalted foolishness outside the binary of sacred or profane.

Premium-grade non-sense is more than just colouring outside the lines; it’s taking the crayon straight up the wall and across the ceiling. It helps us banish the fretful, worrying self we sometimes mistake as our true nature. And when the ego goes AWOL, that slippery other self, the Trickster — who enjoys the game immensely — slips in. As Alan Watts noted, “it’s all about “... the universe thinking itself a tragedy and then surprising itself when it turns out to be a ball.”