Sixteen: The Hardy Question and Its Legacy

ABML casts a light on sixties-era research into spirituality

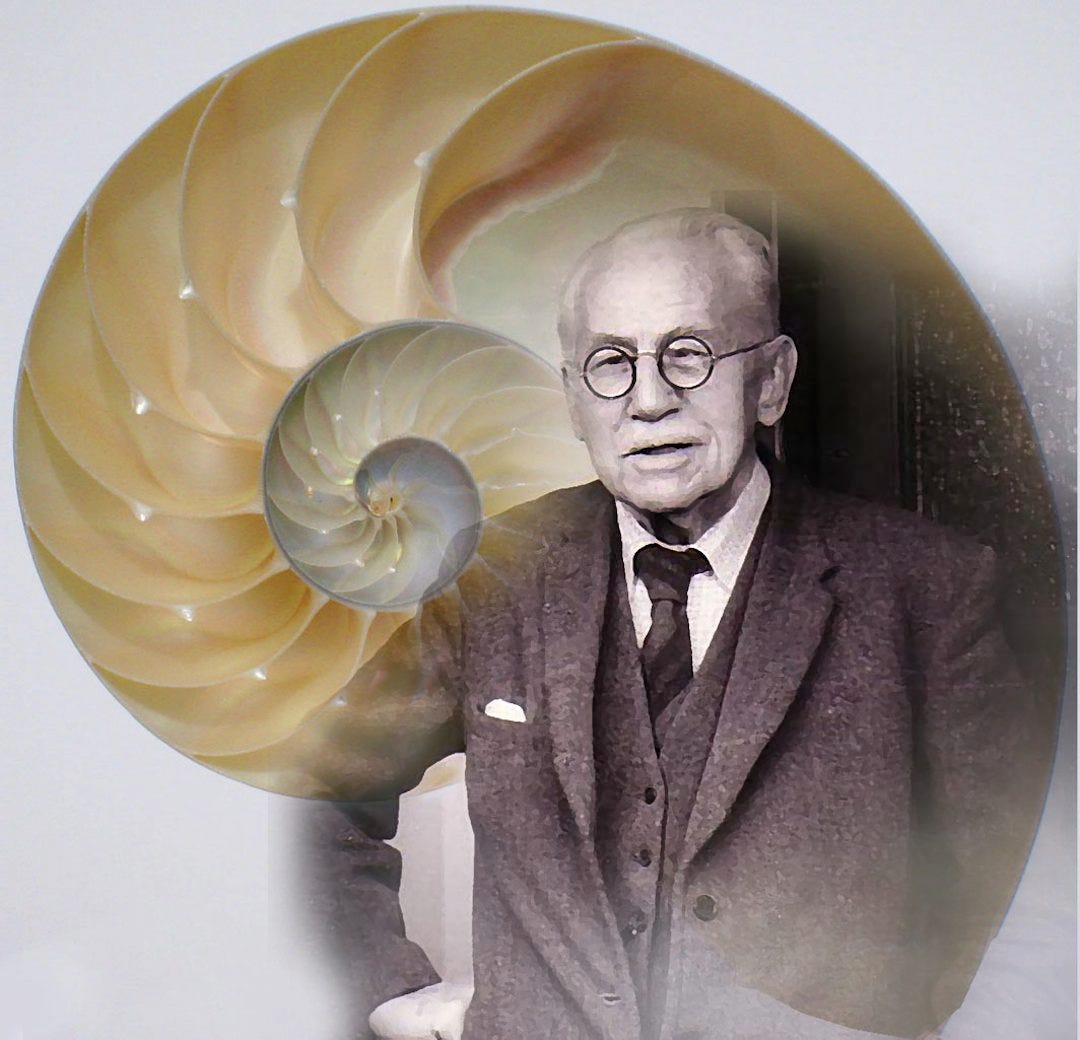

We met the brilliant Alister Hardy in the last installment.

Hardy began his postwar academic career in zoology, and after graduation worked as a naturalist in a fisheries laboratory. From 1924 to 1928 he was chief zoologist for the Discovery Oceanographic Expedition to the Antarctic. A succession of high-end academic postings followed, finishing with the Linacre Chair of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy at Oxford, where his enthusiastic students included a young Richard Dawkins.

Hardy was knighted for his services to the British fishing industry in 1957. Only upon retirement in 1961 did the esteemed marine biologist and author feel secure enough to chart deeper waters.

“All my life I have sampled the sea, building up an ecological picture of a hidden world, which I could not examine at first hand, even with an aqualung. In a way, I am casting my nets into a different kind of ocean,” he told The Observer in 1969.

When Hardy came to Oxford at the peak of his career in the 1940s, he felt that “he needed to be much more circumspect, since he was well aware that some of his colleagues were extremely dismissive of religious beliefs as wrong-headed or infantile,” observed colleague David Hay in his excellent biography, God’s Biologist: A Life of Alister Hardy. As for his scientific opinion on psychic phenomenon, the marine biologist kept his mouth shut, although he remained a discreet member of the Society for Psychical Research for years.

It was not until his retirement in 1960 that the marine biologist felt secure enough to pursue the vow he made as a youth to what he called God: to reconcile science and spirituality in a manner acceptable to the academic world. To this end, he launched the Religious Experience Research Unit at Manchester College at Oxford. He wasn’t particularly interested in psychic experience per se. Rather, he wanted to understand the larger context of spiritual experiences, whether or not they included so-called psychic component.

“Alister Hardy has a legacy and it precedes his work in the study of religion... as just a darn good scientist,” notes Dr. Greg Barker, former director of the Religious Experience Research Centre at the University of Wales. “He developed this solid, methodological approach to things, but he had this intuition that the most important dimension to life was the spiritual dimension. Being a scientist he really wanted to apply a scientific rigour to this... and he had an intuition that there is a lot going on in religious experience that had nothing to do with the church or institutions.

“Of course he waited until he retired; he didn’t want to be seen as a cuckoo by his colleagues because, really, a reductionist Darwinism held force in his day and age. And so if you said there is any other dimension other than a purely biological dimension, you were really dismissed as being a theist or something like that, and he wasn’t a theist... and yet he really believed that there was another dimension than purely biological... but it was rooted in our biology,” Barker told me in a 2013 interview.

Hardy argued that spirituality offered an adaptive benefit for the human species, a different approach than the one taken later by his most famous student, Richard Dawkins. A staunch atheist, Dawkins argues in his book The God Delusion that at this stage of cultural evolution religious experiences and beliefs are maladaptive mass delusions. Was the former student rebelling against his prof’s post-retirement paradigm?

“Dawkins has never commented on this aspect of Alister Hardy‘s work. I’m not sure if he even knows about it or if he’s holding his tongue about it. Because Hardy was a well-loved teacher and leader in biological sciences at Oxford,” Barker offers.

As the American philosopher Daniel Dennett noted in his book, Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, “Hardy could hardly have been a more secure member of the scientific establishment.” Once asked how many things were named after him, “the biologist replied there was a boat in Hong Kong, an octopus, a squid, an island in the Antarctic and – Hardy would add, lowering his voice in a tone of comic embarrassment – two worms.”

A God Within

In 1969, the retired professor and Gifford lecturer leveraged his reputation and renown to petition Manchester College at Oxford University for funds and research space to launch his Religious Experience Research Unit. The college half-heartedly offered Hardy a closed candy shop on the grounds and the rooms above it. It was an inauspicious start to a project that has waxed and waned over the years and continues to this day.

In 1969, the RERU posted what became know as the Hardy question – “Have you ever experienced a presence or power, whether you call it God or not, which is different from your everyday self?” – in a number of religious publications, including The Catholic Herald, The Church Times, and The Methodist Recorder. Only 250 replies came through, mostly from elderly women. The aging plankton expert never feared he was chasing phantoms, but now he was concerned he was tracking a phenomenon that was on the wane in a skeptical, secular age.

The research team had much greater success when Hardy used his connections to the mainstream press to post the question in The Times, The Guardian, The Observer and the Daily Mail. Thousands of responses followed from religious, agnostic and even atheistic readers.

Ironically, one of the first findings by Hardy and his team was that churchgoers were less likely than the general population to have spiritual experiences and those that did were likely to be educated, well-balanced, positive people. Surveys since then indicate that although church attendance has been waning over the past 30 years, spiritual experiences are on the rise, particularly among the young.

“What you find is as you move up the educational scale you get more and more people reporting such experiences,” noted Dr. David Hay In a mid-seventies interview with Irish Radio. “The group in which these experiences are most commonly reported is among university graduates and it’s least commonly reported amongst the most poorly educated.”

Hardy was an empiricist at heart, who began with the most primary datum of experience: his own. Based on his youthful experiences in the woods of Northamptonshire, he believed in the value of transcendent human experiences, which establishment culture generally addressed only in withering or dismissive terms.

The marine biologist’s radical concept of human possibilities extended well beyond the manicured gardens of theology or the intellectual track fields of psychology, sociology and anthropology. “I think telepathy is just as great a discovery as gravity,” he said in a 1971 BBC interview. “Linking together minds is something as fundamental in the universe as gravity.”

When he came to Oxford at the peak of his career in the 1940s, “Alister felt that he needed to be much more circumspect, since he was well aware that some of his colleagues were extremely dismissive of religious beliefs as wrong-headed or infantile,” observed colleague David Hay God’s Biologist. As for his scientific opinion on psychic phenomenon, the marine biologist kept his mouth shut, although he remained a discreet member of the Society for Psychical Research for years.

He argued that human beings are more than just bags of protoplasm with a best-before date, struggling to survive in a random, meaningless cosmos, but he did so within the constraints of evolutionary theory.

In his Gifford Lecture series, “The Living Stream,” the retired prof argued in favour of evolutionary theory, yet against biological reductionism. Living creatures were more than just Darwin’s wind-up toys, and human spirituality was not merely a species-specific overshoot of primitive superstition, turbocharging tribalism and war - as Dawkins and others would argue decades later. To the contrary, these unusual states of mind often granted a fundamental sense of cosmic belonging. They often create social capital by facilitating compassion and openness. Spirituality is arguably often adaptive, not counteradaptive.

For all the intellectual errors and social crimes of organized religion – which Hardy acknowledged – the private spiritual experiences of individuals ‘worked’ because they drew on something deeply embedded in the human psyche. Unfortunately, the marine biologist’s musings went over like a lead balloon with most of his colleagues. “His words were taken as the amiable eccentricities of an otherwise brilliant man, and hence they were tolerated, then ignored,” David Hay noted.

Trained as a zoologist, the aging scholar attempted a taxonomy of spiritual experiences, by breaking the stories gathered in the growing RERU archives down into discrete categories with cross-referenced patterns, similar to the way he had identified and categorized zooplankton as a younger man in his beautifully illustrated books on marine life. His efforts were suggestive, but incomplete.

Since the period of the Enlightenment, philosophers and social scientists have studied religions as a “natural and almost universal human error,” noted David Hay in a 1991 lecture. Unfortunately, Hardy’s choice to use the words “religious” and “spiritual” interchangeably has hampered the understanding of his work and the subsequent research to the present day.

“Alister persisted to the end in labeling such experience ‘religious,’ but his own claims for universality make this seem not quite right. People who reject religion are not thereby denied a universal part of human biology, therefore it is less confusing to refer to such experience as ‘spiritual’ with ‘religious’ experience as a sub- set within that category,” observed Hay.

“Like the people who write to me, I, too, have the sense of being in touch with something bigger than myself,” the marine biologist recounted in a BBC interview in his seventies. “My own religious experiences have been Wordsworthian in feel – the feeling of exaltation at seeing sunlight through young lime trees, for example. I am frankly religious. Of course I don’t think of God as “an old gentleman” out there. I do go to church services but they are not necessary to my religion.”

Hardy’s I-Thou relationship with the natural world and his passionate interest in the objective study of marginalized human experiences seemed aligned much less with fanaticism than with enthusiasm – a word that literally means “a God within.”

The legacy

On his 89th birthday, Hardy received a telephone call informing him he had won the Templeton Prize, considered to be the Nobel Prize of science-and- spirituality studies. Months after Hardy’s surprise birthday gift, 700 guests gathered at London Guildhall for the awards ceremony. The Duke of Norfolk arose to tell the audience that Sir Alister was unable to attend, after suffering a severe brain hemorrhage the day before the presentation. Hardy passed away a few days after the awards.

In his 1971 BBC interview, Hardy noted that most of the reports gathered by his research team were from Britain, the US and Western European countries. “But I’m hoping later on to get many from the Oriental countries. When I’ve got more money, I can actually have the help of oriental scholars.”

Money from the Templeton Prize, which was funneled into the Alister Hardy Trust, allowed the marine biologist’s objectives to outlive him. In 2007, professors Paul Badham and Xinzhong Yao released the results of a study on the religious experiences among China’s population, which not only fulfilled the wish Hardy expressed in the 1971 BBC interview, but also supported his thesis on the universality of patterns in human spiritual experience.

In the end, Hardy’s work was unwelcome at both poles of culture, by religious ideologues and scientific materialists alike. He argued that human beings are more than just bags of protoplasm with a best-before date, struggling to survive in a random, meaningless cosmos, but he did so within the constraints of evolutionary theory. He also believed science could give credence to personal spiritual experiences, as beneficial states of mind, if not glimpses into a wider reality in which we are embedded.

Hardy’s colleague David Hay notes the host of expressions of love and gratitude after Hardy’s death, some of them preserved in the archive of the Bodleian Library. Writes one former student: “His greatness seems to me in some way linked to his childlike approach to life, his tremendous respect for, and wonder at every tiny part. I wish I could have known him better, but I am very grateful for having known him at all.”

Since the marine biologist’s death in 1985, the Alister Hardy Trust continues his legacy. Its objective is “to make a disciplined and as far as possible scientific investigation into the nature, function and frequency of reports of transcendent or religious experience and spirituality in the human species; to investigate their importance in what it means to be human and to disseminate its findings.”

The Trust supports two separate bodies: the Religious Experience Research Centre at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David and the Alister Hardy Society for the Study of Spiritual Experience, which publishes a bi-annual journal, De Numine.

It's interesting that Hardy's legacy seems somewhat like an echo of Emanuel Swedenborg's, in the sense that the material sciences occupied both men for the earlier to middle part of their lives, for then an interest in spirituality to occupy them in the latter. And both applying the mental disciplines to this that they had gained from the former. And this is somewhat an echo of the traditional values and life path of an East Indian householder, who attends to family and secular matters for the the same period, for the then hallowed transition to the spiritual quest in twilight years. There's a great interview that your article reminds me of, maybe the most compelling accounting of personal experiences I've seen; it's the interview of "Shaman Oaks", on a youtube channel of the same name, with a guy called Peter Panagore. Seek it out of you get the chance.